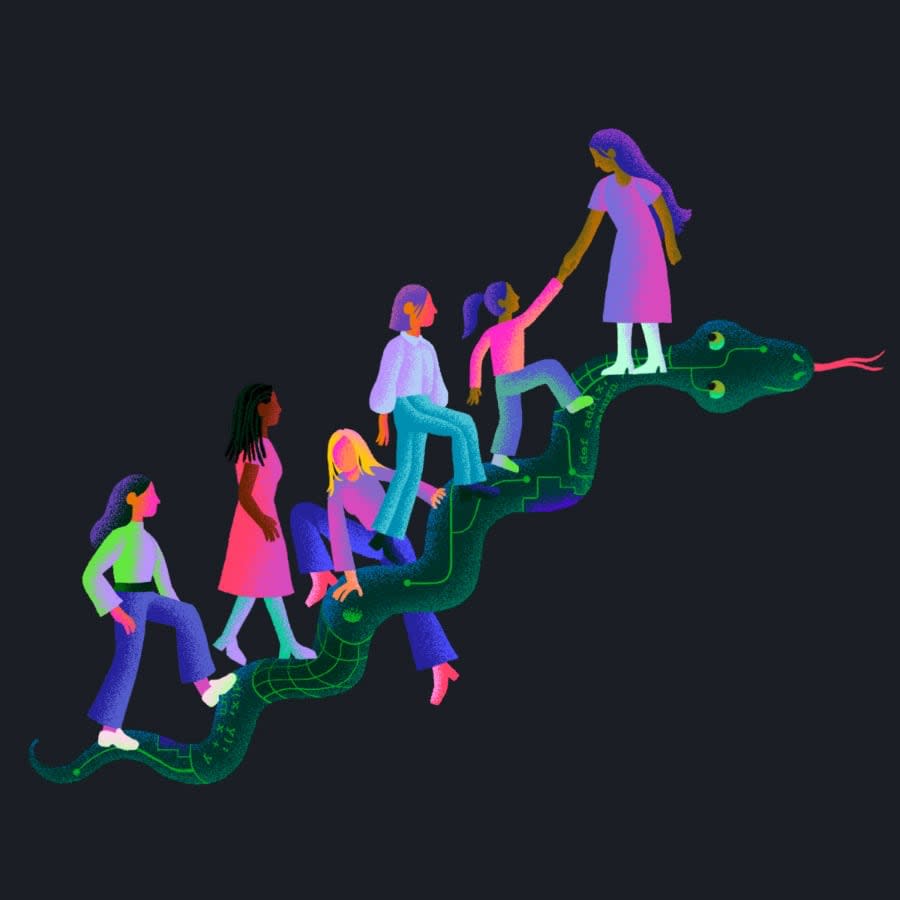

Jessica Upani discovered the open source programming language Python at the PyCon Namibia conference in 2015. She was a mathematics and computer science student at the University of Namibia at the time, but her school work focused mostly on Java. “The conference was free, so I thought ‘why not?’” she says.

By the end of the four-day conference, she had learned enough to write a small program. “I loved that I could build something so fast,” Upani says. “And I loved the community. I wanted to share that experience with others.”

So she founded PyLadies Namibia, a chapter of an international group dedicated to supporting women in Python through mentoring, workshops, meetups, and other events. Today Upani is part of the PyLadies Global Council, working to bring the joy of Python to women around the world through its more than 90 active chapters in more than 33 countries.

Groups like PyLadies play an increasingly important role in bringing more women into open source. It’s no secret that women are underrepresented in tech. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, women make up only 21% percent of computer programmers in the US. But open source is even less balanced.

That means the open source community is missing out on the efforts of qualified contributors, as well as the diversity of perspectives that having more women involved with a project can bring.

For the past several years, Python community leaders have made an effort to bring more women into open source—and into Python, in particular. And those efforts are paying off. In 2011, women gave just 1% of talks at the annual PyCon conference. By 2016, 40% of PyCon talks were given by women and that number has held steady since. In 2015, none of Python’s core developers were women. Now there are six.

“Inclusion increases the quality of the language,” says Carol Willing, a Python core developer and member of the project’s steering council. “Different people bring different skill sets, whether that’s technical skills, project management, leadership, or conflict resolution.”

There are other projects that have a higher percentage of women involved. Half the stewards of p5.js, a JavaScript library for creative projects, are women. But what makes Python exceptional is its age and its scale. Python was first released by Guido Van Rossum in 1991 and has grown to become one of the most popular programming languages in the world, with countless contributors to an ecosystem of libraries, frameworks, and other tools. The lessons the Python community has learned along the way can help other maintainers foster more inclusive communities.

Building a friendly open source experience

Python has a few technical advantages that make it more beginner friendly than many other languages. “From the beginning, Guido designed it to be a very concise and readable language,” Willing says.

A little bit of knowledge goes a long way for novices learning Python. But it isn’t just a beginner’s language. Many professionals use it for advanced work in web development, machine learning, data science, and other disciplines. The fact that it’s easy to learn but powerful to use is part of why Python is more popular than ever, 30 years after its inception.

But Python’s reputation for friendliness can’t be chalked up to technical features alone. The community has made a concerted effort to welcome people of all skill levels.

The team’s other efforts to make Python more inviting range from tweaking their process to rewriting their workflow. For example, in early 2016 the Python core development team began migrating away from a custom, self-hosted development process to GitHub, in part to make the project more accessible to new contributors. “The GitHub toolchain and workflow is familiar to many developers, so they don’t have to learn a completely new workflow just to submit a pull request,” Willing says.

In 2018, Python launched a forum as a place to get support or start discussions outside of its sizable mailing list. “Having smaller spaces for folks to ask for help is really critical because not everyone feels comfortable asking a question on a big mailing list,” Willing says. Many users also find the forum format more accessible. “It handles the presentation of long threads in a more approachable way,” she says. “And it’s easier to see what people have already asked or said.”

Putting a stake in the ground on representation

As important as it is to create welcoming spaces, community leaders also need to actively recruit women into those spaces.

Willing credits Jessica McKellar, a former director of the Python Software Foundation board of directors, for welcoming more women to PyCon events. “She put a lot of personal time and energy into encouraging women to submit proposals and asking people to participate in the community,” Willing says. It takes this sort of proactive work to bring women into the fold.

In 2015, Van Rossum, garbed in a PyLadies t-shirt, announced at PyCon Montreal his goal of recruiting at least two women to the core Python development team in the next two years. The first to join the team was Mariatta Wijaya, who was in the audience that year thanks to financial aid from PyLadies. Van Rossum’s keynote piqued her interest, but she credits his personal mentoring for helping her make the leap. “If you’re in a position to recruit and mentor people, I think you should try hard to actively seek out women for those roles,” Wijaya says.

Making these sorts of efforts especially important for a community like Python that extends far beyond any single project or team to an entire ecosystem of libraries, frameworks, and other tools. “Many people look to the technical leaders for inspiration and guidance, so Guido wearing the t-shirts, putting a stake in the ground and saying ’I want women developers’ made a difference,” Willing says.

Organizing supportive communities

Grassroots organizing within the community also plays a large role in shaping the Python experience around the world and PyLadies is a key part of that. “When I started learning Python, I only knew maybe two people who knew the language,” says Marie-Louise Annan, who is now a professional data scientist and vice-chair of the PyLadies Global Council. “So I joined the PyLadies Remote chapter, because I’m a mum and can’t do in-person meetups. PyLadies was huge for me. I could see women like myself who were on this journey of becoming programmers and it made me excited to help.”

A common barrier for people trying to get into open source is finding out how they can contribute. “It’s not always clear what the different opportunities are,” Annan says. One big goal for PyLadies is to help shine a light on all the ways that women can contribute to Python. “It’s not just core development, which is brilliant but there are other areas,” she says. “You can work on community building, event organizing, or communications.” Even core development often involves aspects other than coding, like reviewing pull requests and coordinating projects. Most projects can do a better job of outlining what sorts of roles prospective contributors can take on.

Including women isn’t just about growing their numbers. It’s also about helping them contribute by creating more supportive communities—an increasingly important goal for PyLadies. As the organization scales up, it plans to provide more resources to its various chapters, whether that’s funding, training, or mentorship opportunities for regional chapters. “We’re building a platform for women in every country to support each other and learn in their own way,” Upani says.

That means building an organization that represents all women, regardless of where they live. To address this, the PyLadies Global Council adopted a rule that only 1/3rd of its members can be from the same country—that’s three out of nine members for now. The election site is available in seven different languages.

Not every project has the global reach and scale of Python and PyLadies. But everyone can learn a few lessons on inclusivity, representation, and communibuilding from Python’s growing ecosystem.