⚠️ Caveat Plagiarius: Certain universities in spa cities have reported instances of plagiarism involving this repository. Please remember that plagiarism is cheating, and using this solution as-is will not succeed as the marking method has since changed. Feel free to use this code for reference, but do your own research and create your own work.

An agent to solve sudoku puzzles by approaching them as exact cover problems, made for my Artifical Intelligence module. On my machine, it can solve a "hard" sudoku in under 7 milliseconds. This work was awarded 100%.

Your submission passed all of our tests with flying colours and within the time limit, even on the hardest sudokus. Very ambitious and interesting choice of algorithm - well done for pulling it off! Your readme shows very high levels of technical and conceptual sophistication, well done. Extremely strong work. Well done. The difference between the very top grades is just down to time and presentation.

Final grade: 100/100

To obtain a solution, pass sudoku_solver a numpy.ndarray((9,9), ...). Examples of input can be found in /data.

import numpy as np

sudoku_state = np.ndarray((9, 9), ...) # Set values to sudoku grid to solve.

solution = sudoku_solver(state=sudoku_state)

print(solution) # This will print the solution, or a 9x9 grid of '-1'.This was a deeply engaging and educative challenge that I spent a lot of time on, and I'm very proud of the results. I made two attempts: The first to get my head around backtracking, constraint-propagation and reducing processing time; the second to approach the problem differently to meet the sub-one-second target.

My first attempt was a simple backtracking algorithm that would recursively try each of a cell's possible values, and update the associated cells' possible values accordingly. This was a simple implementation of backtracking and constraint-propagation.

The first time this worked it took the agent about 40 seconds to solve a single "hard" puzzle. I was happy to find that my code was working, though I wanted to aim to solve a single puzzle in under a second on my machine.

After optimisations including simplifying loops, caching, forward-checking, value frequency analysis and implementing a

specialised deepcopy function, I got this time down to about 2 seconds: a lot closer, but still too slow.

I decided to start again, and learnt how to approach sudokus as exact cover problems (mainly thanks to Andy G's 2011 blog post). My first implementation of Donald Knuth's (2000, p.4) Algorithm X resulted in a hard sudoku taking 10 seconds.

This was worse than my previous best, but a lot better than my previous first attempt. Through similar (but fewer) optimisations (includng the complete removal of deep-copying objects), my submission now takes less than 7 milliseconds to solve a "hard" sudoku puzzle.

This document will mainly focus on methodologies present in the second attempt, but will still occasionally reference the first.

An exact cover is a collection of subsets of S such that every element in S is found in exactly one of the

subsets. (Dahlke, 2019)

Given a set S and the subsets A, B, C, D, E:

-

S = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7} -

A = {1, 6, 7} -

B = {1, 3, 5} -

C = {2} -

D = {3, 4, 5} -

E = {1, 2, 3, 4}

Then the exact cover of S is the sets A, C, D:

-

A ∪ C ∪ D = S(The subsets cover every element inS) -

A ∩ C ∩ D = {}(Every element inSis covered by only one set)

Before we discuss how we solve sudokus specifically, let's explore how to solve a general exact cover problem.

Algorithm X solves exact cover problems by using a matrix A, consisting of 1s and 0s. Let's put the above example

in such a matrix...

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| B | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| C | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| D | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| E | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

The algorithm is as follows:

If A is empty, the problem is solved; terminate successfully.

Otherwise choose a column, c (deterministically).

Choose a row, r, such that A[r, c] = 1 (nondeterministically).

Include r in the partial solution.

For each j such that A[r, j] = 1,

delete column j from matrix A;

for each i such that A[i, j] = 1,

delete row i from matrix A.

Repeat this algorithm recursively on the reduced matrix A.

Knuth's (2000, p.4) Algorithm X

In simpler terms, the algorithm takes an element e to cover, and finds a row which does so. This row is added to the

solution, and every row that also covers e is removed from A, along with every column that the chosen row also

satisfies.

Selecting row A, and doing this described reduction leads to the reduced matrix A:

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| D | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Solution = {A}

- Row

Awas removed and added to our solution. - Rows

BandEwere removed because they also covered element1. - Columns

1,6,7were removed because they were covered by rowA.

You can see how doing the same steps again will reduce this matrix further, and will lead to a valid solution being found.

To approach sudoku as an exact cover problem, you must step back from the sudoku grid, and think about what a solved sudoku contains:

- A set of filled cells

- A set of rows, each with one of each number

1-9 - A set of columns, each with one of each number

1-9 - A set of blocks, each with one of each number

1-9

... and we can also think about what it means to write a value v to a cell (row, column) in the sudoku grid:

-

This unique RCV (Row, Column, Value) will help to satisfy a unique combination of the constraints listed above.

-

No other cell in the grid should satisfy the same constraints, as this would mean there were duplicate values. (i.e The constraint "Row 1 should contain the value 5" should only be satisfied once).

-

... so every constraint needs to be satisfied by exactly one RCV triple.

This is now an exact cover problem - every element in our set of constraints needs to be covered exactly once!

From what we've realised from the nature of sudoku puzzles, we can construct our matrix A to represent our constraints

and associated RCV combinations. The following is a few rows and columns from the large (324 x 729) matrix:

| Constraints | 0,0,1 | 0,0,2 | 4,4,1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell 0,0 has a value | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Cell 0,1 has a value | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Row 0 contains a 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Row 0 contains a 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Col 0 contains a 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Col 0 contains a 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Block 4 contains a 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

Now that we have our matrix A, we can apply Algorithm X to generate solutions.

Note: I learnt a majority of this from Andy G.'s (2011) excellent explanation

Note: Due to python naming conventions, the matrix

Ais referred to asathroughout my code.

After sudoku_solver is passed the initial state, it passes it to backtrack, which is the main worker function. This

is where Algorithm X is executed.

pick_constraint will find the constraint with the smallest number of satisfying RCV tuples. These values are tested in

turn, just as described before.

Algorithm X is a backtracking function - it exploits the nature of recursing (and "un-recursing") to find the correct solution.

You can see the backtracking function here:

def backtrack(state: SudokuState) -> SudokuState or None:

"""

Solve sudoku using backtracking

:param state: State to solve

:return: Solved state

"""

# Pick a constraint to satisfy

const = state.pick_constraint()

# No more constraints to satisfy

if const is None:

return None

# List of satisfying RCV (row, column, value) tuples

satisfying_rcvs = list(state.a[const])

for rcv in satisfying_rcvs:

# Add RCV to solutions, and save removed conflicting RCVs

removed = state.add_solution(rcv)

# Return this state if it's a goal

if state.is_goal():

return state

# Continue trying this RCV

deep_state = backtrack(state)

# Was a solution found?

if deep_state is not None:

return deep_state

# This RCV doesn't lead to a solved sudoku

# Remove RCV from solution and restore the matrix, so that we can try the next RCV

state.remove_solution(rcv, removed)If the first RCV that is tested doesn't lead to a goal state, the algorithm will backtrack and any changes made to the

SudokuState object will need to be abandoned.

Initially this was achieved by creating a deep copy of the SudokuState object at each level of the recursion, creating

independent copies of mutable fields (namely A). However, creating these copies was inefficient and slowed the

algorithm down significantly.

After attempting to fix this by writing a new, specialised, and therefore faster deepcopy

function, I decided it would be better to use the same object, and instead store changes to the matrix in the

appropriate recursion level in a list named removed. As the algorithm works back up the recursion levels, it will

undo these changes by calling remove_solution, restoring the matrix back to how it was for the level above it.

The act of removing rows and columns from matrix A after a row is chosen is a strict and efficient way of propagating

constraints.

If the agent receives an empty grid, it will generate a random solved sudoku. I don't know if this will always be the

same, but the following is the grid that it consistently returns on my machine. Perhaps different versions of python

will convert a set to a list differently: this is the only "random" aspect of my program that I can think of.

[[4 7 1 3 8 6 5 9 2]

[9 3 2 5 4 7 6 1 8]

[8 5 6 2 1 9 7 4 3]

[2 9 3 1 6 8 4 5 7]

[6 8 7 9 5 4 3 2 1]

[1 4 5 7 3 2 8 6 9]

[7 6 9 8 2 5 1 3 4]

[3 2 4 6 7 1 9 8 5]

[5 1 8 4 9 3 2 7 6]]

If the agent receives a full grid (with no 0 values), an error grid is returned, regardless of whether the

received sudoku is a goal or not. This is a sudoku solver, not a sudoku checker.

Note: Not all the following are in my final solution.

Before using Algorithm X, I decreased the processing time significantly by caching rows, column and blocks that had

already been validated in a shared dictionary for all puzzles. Rows, columns and blocks can all be considered

equivalent, as they all require one of each value 1-9, regardless of order. Blocks were flattened to make them

equivalent to rows and columns.

Part of the success of this optimisation was the fact that the algorithm would spend slightly longer on the faster puzzles (those classed as "very_easy", "easy", or "medium") to speed up the processing of the slower puzzles.

It was faster to store the permutations (where order matters) instead of the combinations (where order doesn't matter), so the algorithm would generate 24806 permutations from the testing data, compared to the 520 possible combinations. This obviously increased space complexity of the algorithm dramatically, but processing time was my main priority.

Now that the code uses Algorithm X, there is no need to check for valid combinations of numbers, so there currently is no caching.

Profiling my code uncovered the fact that deepcopy was taking up the most processing time, so I needed to reduce the

time it took.

As the copy.deepcopy function is made to make an independent copy of an arbitrary object, it will be doing a lot

of unnecessary processing in most cases. Looking at the source code in copy.py shows the amount of checks that occur

everytime a copy is made. These checks would be necessary if the object I was copying contained references to itself

(Python Software Foundation, 2021), however in this particular case, it doesn't.

Writing a new deepcopy method was as simple as creating a new object of the same class, and setting the fields to the

values of the copied object.

Here is what the specialised deepcopy looked like.

def __deepcopy__(self, memodict={}):

"""

Perform a deepcopy on SudokuState.

IMPORTANT: New fields added to the class SudokuState also need to be added here.

:return: New object

"""

cls = self.__class__

state = cls.__new__(cls)

state.values = self.values

state.a = {k: set(self.a[k]) for k in self.a.keys()} # set() appears to be quicker than copy()

state.solvable = self.solvable

state.solution = self.solution

return stateNote: This is a precise, fast and error-prone way of copying an object. This approach requires you to update

deepcopyevery time a new field is added to the target class.

The new deepcopy being used for a while in my second attempt, though now it uses the add_solution, remove_solution

functions to make and abandon changes made to the same object through the recursions, by calling

remove_conflicting_rcvs, and restore_rcvs respectfully.

To reduce bugs and improve readability, I was using enums for constraints. This meant that typos would be instantly recognised. However, using strings is much faster.

After researching online, I found that Python's slow enums have been discussed, and were at one point 20x slower than normal lookups (Python 3.4) (craigh, 2015). This has been fixed, though there is still an open issue on the python bug tracker complaining about the speed for Python 3.9. (MrMrRobat, 2019)

I converted all enums to strings at the end of development of my second attempt.

-

Depth-first search, constraint propagation and forward checking

-

Exact cover and Knuth's Algorithm X

-

Implementing previously-theoretical Ideas

-

Python's enums are Slow

-

How to spell "sudoku"

Early attempts at this project included functionality to solve sudokus that weren't the standard 9x9 grid. As this feature would be untested, and most likely riddled with bugs, I decided that for my final submission I should submit code with the 9x9 grid assumed and expected throughout.

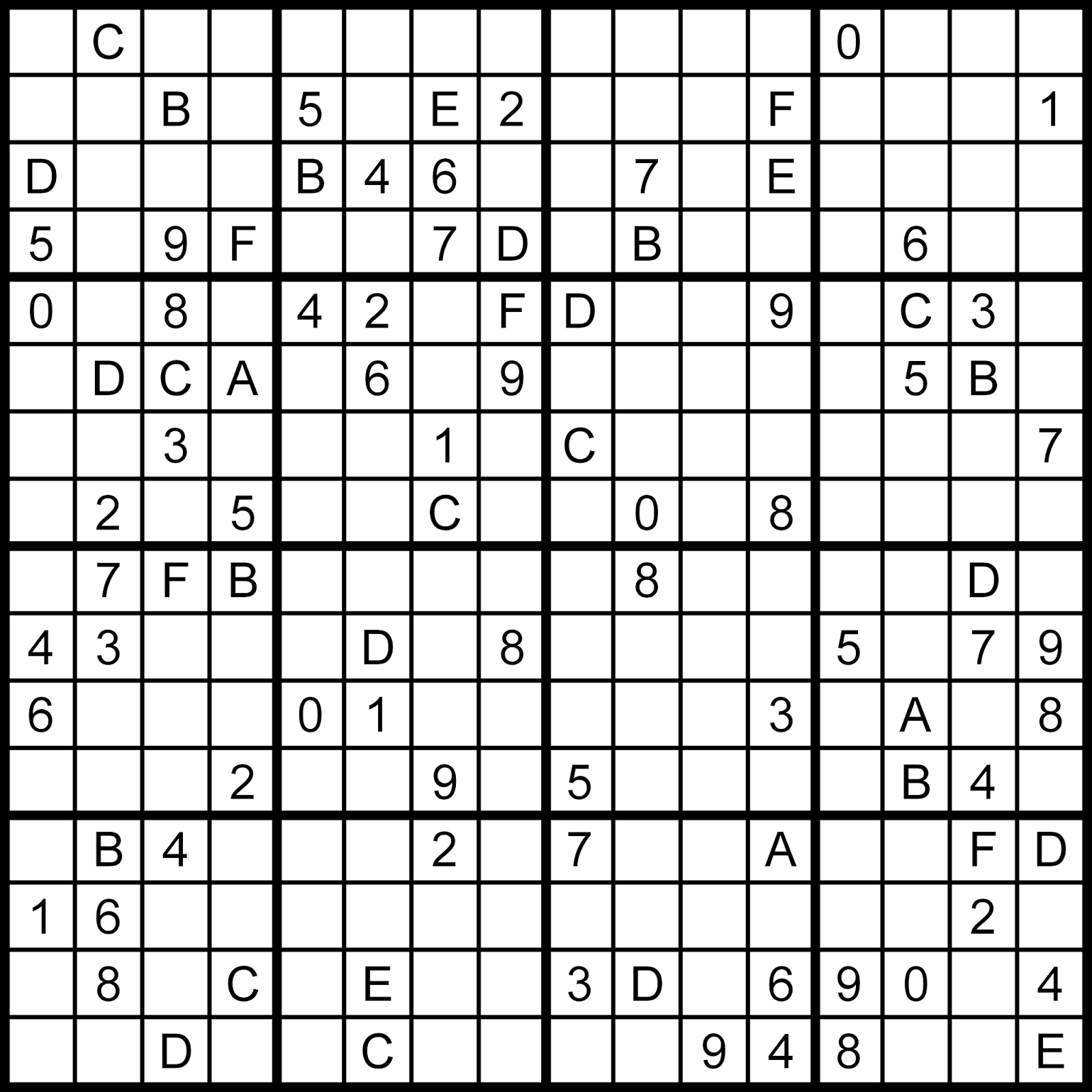

I believe it would be a good exercise to re-implement the lost generality: perhaps I could aim to solve 16x16 hexadecimal sudokus, such as this one:

(mattspuzzleblog, 2014)

Multi-threading could also be implemented, to test different rows of the matrix simultaneously.

Knuth, D. 2000. Dancing Links. Millenial Perspectives in Computer Science, 2000, 187--214, Knuth migration 11/2004, pp 4

Dahlke, K. 2019. Exact Cover [Online]. Available from: https://www.mathreference.com/lan-cx-np,excov.html [Accessed 11 March 2021]

G, Andy. 2011. Solving Sudoku, Revisited [Online]. Andy G's Blog. Available from: https://gieseanw.wordpress.com/2011/06/16/solving-sudoku-revisited/ [Accessed 11 March 2021]

Python Software Foundation. 2021. copy — Shallow and deep copy operations [Online]. Python 3.9.2 Documentation. Available from: https://docs.python.org/3/library/copy.html [Accessed 11 March 2021]

craigh, 2015. Enum member lookup is 20x slower than normal class attribute lookup [Online]. Available from: https://bugs.python.org/issue23486 [Accessed 11 March 2021]

MrMrRobat, 2019. Increase Enum performance [Online]. Available from: https://bugs.python.org/issue39102 [Accessed 11 March 2021]

mattspuzzleblog, 2014. 2014-01-22 Hexadecimal Sudoku Available from: http://mattspuzzleblog.blogspot.com/2014/01/2014-01-22-hexadecimal-sudoku.html [Accessed 11 March 2021]