Transitioning from GLSL to WGSL

Magnus Thor, 17th of December, 2024

ShaderToy among others have for long been the playground for shader enthusiasts. With just a browser and a few lines of GLSL code, we’ve created mesmerizing visuals, learned the intricacies of GPU programming, and pushed the boundaries of real-time rendering. But as WebGPU emerges as the next-generation web graphics API, WGSL (WebGPU Shading Language) is stepping into the spotlight.

So why should ShaderToy fans care about WGSL? The answer lies in WebGPU’s potential. WGSL is designed for modern GPU pipelines, offering more safety, structure, and performance optimization opportunities than GLSL. While transitioning from GLSL to WGSL may seem daunting at first, it’s also a chance to evolve and leverage your ShaderToy expertise in the new ecosystem.

This guide will briefly describe how you translate your GLSL knowledge into WGSL with practical examples and a ShaderToy perspective. Whether you're a casual shader tinkerer or a serious graphics programmer, it may be worth reading, i dont know, i'm sharing my experiences in the subject.

WebGPU is a modern graphics API designed for the web, bringing significant improvements over older technologies like WebGL. From a WGSL perspective, these advantages are clear:

Safety: WGSL enforces stricter rules than GLSL, making your shaders more robust and less prone to errors. For example:

- Strict Type Checking: WGSL enforces type compatibility more rigorously, catching potential errors during compilation that might lead to unexpected behavior in GLSL.

- Bounds Checking: WGSL performs bounds checking on array and texture accesses, preventing out-of-bounds errors that can cause crashes or unpredictable results in GLSL.

- No Undefined Behavior: WGSL defines the behavior of operations more precisely, eliminating undefined behavior that can make GLSL code unpredictable across different hardware.

Structure: WGSL promotes well-structured code through features like:

- Structs: You can define custom data structures (structs) to organize your shader data, improving code readability and maintainability.

- Modules: WGSL allows you to organize your shader code into modules, promoting better code separation and reusability.

- First-Class Functions: Functions are treated as first-class citizens in WGSL, enabling more modular and organized code compared to GLSL.

Performance: WGSL is designed with performance in mind.

- Closer to the Metal: WebGPU (and WGSL) are designed to be closer to modern graphics APIs like Vulkan and DirectX . This allows browsers to leverage the full capabilities of the underlying hardware more efficiently than with OpenGL.

- Reduced Driver Overhead: WebGPU's architecture minimizes driver overhead, allowing for more direct access to GPU resources and potentially faster execution.

- Optimized Compilation: WGSL's design facilitates better compiler optimizations, leading to more efficient shader code execution.

These features contribute to WebGPU's goal of providing high-performance graphics on the web, making it a compelling choice for demanding applications like shader art, games, simulations, and data visualizations.

If you’ve spent hours crafting shaders in ShaderToy, you’re probably familiar with GLSL’s concise and flexible syntax. WGSL, however, introduces some stricter rules and a slightly different structure to ensure safety and compatibility with WebGPU.

Here’s a quick comparison of a ShaderToy-style GLSL fragment shader and its WGSL counterpart:

uniform vec3 iResolution;

uniform float iTime;

void mainImage( out vec4 fragColor, in vec2 fragCoord )

{

vec2 uv = fragCoord/iResolution.xy;

vec3 col = 0.5 + 0.5*cos(iTime+uv.xyx+vec3(0,2,4));

fragColor = vec4(col,1.0);

}

void main() {

mainImage(gl_FragColor, gl_FragCoord.xy);

}

struct VertexInput {

@builtin(position) pos: vec4<f32>,

@location(0) uv: vec2<f32>

};

struct Uniforms {

resolution: vec3<f32>,

time: f32

};

@group(0) @binding(0) var<uniform> uniforms: Uniforms;

fn mainImage(invocation_id: vec2<f32>) -> vec4<f32> {

var result: vec4<f32>;

let uv: vec2<f32> = invocation_id / uniforms.resolution.xy;

let col: vec3<f32> = 0.5 + 0.5 * cos(uniforms.time + uv.xyx + vec3<f32>(0., 2., 4.));

result = vec4<f32>(col, 1.);

return result;

}

@fragment

fn main_fragment(in: VertexInput) -> @location(0) vec4<f32> {

return mainImage(in.pos.xy);

}Even in this simple example, you can notice some core differences between GLSL and WGSL:

-

Explicit Types: WGSL requires explicit types for all variables and literals. See those suffixes and the 0.0, 2.0, 4.0 in the vec3 constructor? They tell WGSL we're working with 32-bit floating-point numbers. This strictness helps catch errors early on.

-

Entry Point Attributes: The @fragment attribute in WGSL marks the main function as the entry point for the fragment shader. This is more explicit than GLSL's implicit main function recognition.

-

Uniform Handling: WGSL uses structs and binding attributes (@group, @binding) to manage uniforms, textures and samplers, providing a more structured and organized way to pass data to your shaders.

-

Built-in Variables: WGSL uses @builtin(position) to access the fragment coordinates, while GLSL relies on the built-in variable gl_FragCoord.

These are just a few initial glimpses into WGSL's syntax. As we delve deeper, you'll discover more about its unique features and how they contribute to writing robust and efficient shaders.

in: Read-only parameter passed by value.out: Parameter passed by reference, modified inside the function, and returned.inout: Combination ofinandout; the parameter is read and modified.

void modifyColor(in vec3 inputColor, out vec3 outputColor, inout float brightness) {

outputColor = inputColor * brightness;

brightness *= 0.9; // Diminish brightness

}

void main() {

vec3 color = vec3(1.0, 0.0, 0.0);

vec3 result;

float brightness = 1.5;

modifyColor(color, result, brightness);

}WGSL handles mutability explicitly through references and explicit returns, and does not support GLSL-style out or inout parameters. Here’s how the above GLSL example translates:

fn modifyColor(inputColor: vec3<f32>, brightness: ptr<function, f32>) -> vec3<f32> {

// Dereference and modify brightness

*brightness *= 0.9;

return inputColor * *brightness; // Return modified color

}

@fragment

fn main() -> @location(0) vec4<f32> {

let inputColor = vec3(1.0, 0.0, 0.0);

var brightness: f32 = 1.5;

let resultColor = modifyColor(inputColor, &brightness);

return vec4<f32>(resultColor, 1.0);

}-

Explicit Pointers in WGSL

- WGSL uses

ptr<function, T>to define references for mutable variables. - You must explicitly pass references using

&and dereference them with*.

- WGSL uses

-

No

outorinout- WGSL requires explicit returns for outputs.

- Use pointers when mutating input variables.

-

Immutable by Default

- WGSL variables are immutable unless declared with

var. - For mutable parameters, pointers are necessary.

- WGSL variables are immutable unless declared with

void updatePosition(inout vec3 position, in vec3 velocity, float time) {

position += velocity * time;

}

fn updatePosition(position: ptr<function, vec3<f32>, velocity: vec3<f32>, time: f32) {

*position = *position + velocity * time;

}

@fragment

fn main() -> @location(0) vec4<f32> {

var pos = vec3<f32>(0.0, 0.0, 0.0);

let vel = vec3<f32>(1.0, 0.0, 0.0);

let time: f32 = 2.0;

updatePosition(&pos, vel, time);

return vec4<f32>(pos, 1.0); // pos has been updated

}- Variables declared inside a block are scoped to that block.

- Outer variables can be shadowed (redeclared) by inner variables.

@fragment

fn main() -> @location(0) vec4<f32> {

let value = 5.0; // Outer scope

{

let value = 10.0; // Inner scope (shadows outer value)

// Use `value` inside this block: 10.0

}

// Use `value` outside block: 5.0

return vec4<f32>(value, 0.0, 0.0, 1.0);

} - Pointers (e.g.,

ptr<function, T>) must reference mutable variables (var). - A pointer cannot escape the scope of its referent, preventing dangling pointers and memory leaks.

- WGSL also includes

ptr<storage, T>for accessing data in storage buffers, crucial for complex shader operations. - A pointer cannot escape the scope of its referent.

fn modifyValue(val: ptr<function, f32>) {

*val = *val + 1.0; // Modifies the referenced variable

}

@fragment

fn main() -> @location(0) vec4<f32> {

var counter = 0.0;

modifyValue(&counter); // Pass mutable variable by reference

return vec4<f32>(counter, 0.0, 0.0, 1.0);

}This WGSL code demonstrates how pointers are used within a function's scope to modify a value. Now, let's delve deeper into the nuances of pointers in WGSL and how they contrast with GLSL.

Raymarching shaders are a hallmark of shader-art and showcase the power of procedural rendering. Let’s take a simple raymarching example and walk through its conversion to WGSL.

float sphere(vec3 ro, vec3 rd) {

vec3 spherePos = vec3(0.0, 0.0, 3.0);

return length(ro - spherePos) - 1.0;

}

vec3 normal(vec3 p) {

float d = 0.001; // Approximation factor

return normalize(vec3(

sphere(p + vec3(d, 0.0, 0.0)) - sphere(p - vec3(d, 0.0, 0.0)),

sphere(p + vec3(0.0, d, 0.0)) - sphere(p - vec3(0.0, d, 0.0)),

sphere(p + vec3(0.0, 0.0, d)) - sphere(p - vec3(0.0, 0.0, d))

));

}

void mainImage(out vec4 fragColor, in vec2 fragCoord) {

vec2 uv = fragCoord / iResolution.xy * 2.0 - 1.0;

uv.x *= iResolution.x / iResolution.y;

vec3 ro = vec3(0.0, 0.0, -5.0); // Ray origin

vec3 rd = normalize(vec3(uv, 1.0)); // Ray direction

float t = sphere(ro, rd); // Distance to sphere

if (t > 0.0) {

vec3 pos = ro + rd * t; // Surface position

vec3 n = normal(pos); // Surface normal

vec3 lightDir = normalize(vec3(1.0, 1.0, -1.0));

float diff = max(dot(n, lightDir), 0.0);

fragColor = vec4(vec3(diff), 1.0); // Simple diffuse lighting

} else {

fragColor = vec4(0.0); // Background color

}

}

void main() {

mainImage(gl_FragColor, gl_FragCoord.xy);

} struct Uniforms {

resolution: vec3<f32>,

time: f32

};

@group(0) @binding(0) var<uniform> uniforms: Uniforms;

@group(0) @binding(1) var linearSampler: sampler;

struct VertexOutput {

@builtin(position) pos: vec4<f32>,

@location(0) uv: vec2<f32>

};

// Raymarching parameters

const MAX_STEPS: i32 = 100;

const MIN_DIST: f32 = 0.001;

// Function to compute the distance to the sphere

fn sphere(ro: vec3<f32>, rd: vec3<f32>) -> f32 {

let spherePos = vec3(0.0, 0.0, 3.0);

return length(ro - spherePos) - 2.0;

}

// Function to compute the distance to the plane

fn plane(ro: vec3<f32>, rd: vec3<f32>) -> f32 {

return ro.y + 2.0; // Simple horizontal plane at y = -2

}

// Raymarching function that tests both surfaces

fn raymarch(ro:vec3<f32>>, rd: vec3<f32>) -> vec3<f32>

var totalDist = 0.0;

var hit = false;

var color = vec3(0.0, 0.0, 0.0); // Background color

var steps: i32 = 0;

while (steps < MAX_STEPS) {

let sphereDist = sphere(ro, rd);

let planeDist = plane(ro, rd);

// Use any() to check if both distances are above the minimum distance

let hitCondition = any(vec2<bool>(sphereDist < MIN_DIST, planeDist < MIN_DIST)) ;

if (hitCondition) {

// Use .select to decide which color to apply based on the distance

color = select(vec3(1.0, 0.0, 0.0), vec3(0.0, 1.0, 0.0), sphereDist < MIN_DIST);

hit = true;

break;

}

// Use fma() to accumulate the total distance in one operation (multiply + add)

totalDist = fma(min(sphereDist, planeDist), 1.0, totalDist); // totalDist = totalDist + min(sphereDist, planeDist)

// Move along the ray (raymarching step)

ro = ro + rd * min(sphereDist, planeDist);

steps += 1;

}

// Return color based on whether we hit something or not

return select(vec3(0.0, 0.0, 1.0), color, hit); // Blue background if not hit

}

fn main(fragCoord: vec2<f32>) -> vec4<f32> {

// Normalize pixel coordinates to range [-1, 1]

let uv = fragCoord.xy / uniforms.resolution.xy * 2.0 - 1.0;

let aspect_ratio = uniforms.resolution.x / uniforms.resolution.y;

let adjusted_uv = vec2(uv.x * aspect_ratio, uv.y);

// Camera setup

let ro = vec3(0.0, 0.0, -5.0); // Ray origin (camera)

let rd = normalize(vec3(adjusted_uv, 1.0)); // Ray direction

// Perform raymarching

let color = raymarch(ro, rd);

return vec4<f32>(color, 1.0);

}

@fragment

fn main_fragment(in: VertexOutput) -> @location(0) vec4<f32> {

return main(in.pos.xy);

}After reviewing the basic GLSL and WGSL raymarching shaders, let’s explore how some of WGSL's built-in functions—such as any() and .select()—can simplify and enhance our shader code. These functions are powerful tools for handling conditional logic more efficiently, especially in shaders where performance and readability are crucial.

The any() function in WGSL checks if any conditions in a vector are true. This is particularly useful when you have multiple conditions and want to ensure they are all satisfied at the same time.

In our raymarching shader, we can use any() to check if any of the distances to the surfaces (e.g., sphere, plane) are below the threshold distance (MIN_DIST). If they are, this means we've hit an object, and we can perform the necessary operations, such as assigning the correct color.

let hitCondition = any(vec2<bool>(sphereDist < MIN_DIST, planeDist < MIN_DIST)) This condition checks if both sphereDist and planeDist are less than MIN_DIST, meaning we've hit either the sphere or the plane. The use of any() makes the logic more concise and readable than checking each condition separately.

The .select() function in WGSL allows you to choose one of two values based on a condition. It's like a more elegant way to write an if-else statement in a single line.

In our raymarching shader, we can use .select() to choose the color based on which surface we hit (the sphere or the plane). If the distance to the sphere is below the threshold, we select the color red; if the distance to the plane is below the threshold, we select green.

color = select(vec3(1.0, 0.0, 0.0), vec3(0.0, 1.0, 0.0), sphereDist < MIN_DIST);// Red for place, Green for sphereHere, .select() is used to choose between red (vec3(1.0, 0.0, 0.0)) and green (vec3(0.0, 1.0, 0.0)) based on the distance to the sphere or the plane.

After the raymarching loop, we can also use .select() to decide the background color based on whether we've hit an object or not. If we hit an object (i.e., the hit flag is true), the color is the one we calculated during raymarching. If we didn’t hit anything, the background is blue.

return select(vec3(0.0, 0.0, 1.0), color, hit);// Blue background if not hitThis line uses .select() to return the color we calculated from raymarching if the ray hit an object, or a blue background color (vec3(0.0, 0.0, 1.0)) if the ray didn’t hit anything.

- Efficiency: These functions allow for more compact and potentially more optimized code. They reduce branching and conditional logic, which can be performance-heavy in shaders.

- Readability: Instead of using multiple

if-elsestatements, these functions provide a cleaner, more readable way to handle conditions. - Parallelism: WGSL is designed with parallel execution in mind. Functions like

any(), and.select()help write shaders that work well with the GPU’s parallel processing capabilities.

In WGSL fragment shaders (used in rendering pipelines) automatically benefit from parallelism. Each invocation of the fragment shader runs on a separate thread, which allows the GPU to process many pixels in parallel. This is particularly beneficial when rendering complex scenes, as many parts of the screen can be computed simultaneously.

- Considerations for Fragment Shaders: While fragment shaders benefit from parallelism, they need to be written with the understanding that the order of execution of threads is undefined. This means there’s no guarantee that any two threads will run in the same order, so you need to avoid relying on thread order when writing the shader logic. This is where functions like

any()and.select()come in handy, as they allow for efficient, non-branching logic that runs well in parallel.

- Fragment Shaders: Parallelism is implicit. The GPU handles the scheduling and execution of fragments (or pixels), and shaders are designed to process individual fragments independently.

- Compute Shaders ( Not covered in this post): Parallelism is explicit. You control how work is distributed across threads and workgroups, allowing for more complex calculations, such as physics simulations, image processing, or machine learning workloads.

There are indeed other WGSL functions and considerations worth discussing in the context of parallelism, especially when dealing with control flow and synchronization in shaders. Parallelism in WGSL can introduce certain complexities, particularly when transitioning from GLSL, where control flow (such as if-else statements) is sometimes handled more easily without thinking about parallel execution. However, in WGSL, especially with fragment shaders, parallelism is more explicit, and that can lead to some unexpected behavior if not handled carefully.

Let's break down a few key concepts and functions that can help optimize shaders in parallel environments and avoid common pitfalls.

We've already discussed any(), which checks if all conditions in a vector are true. Similarly, any() checks if any condition is true, and it can be used for handling parallel checks efficiently.

all(): Returnstrueif all conditions are true in the vector.any(): Returnstrueif any condition is true in the vector.

Both functions are ideal for parallel checks, as they minimize the need for branching and can execute efficiently across all threads.

let condition = all(x > 0.0, y < 1.0);

let anyCondition = any(x > 0.0, y < 1.0);These functions can help avoid expensive branching in shaders, especially when multiple conditions need to be checked in parallel.

As mentioned earlier, .select() is a powerful function that can replace if-else logic. It is essential in a parallel environment to minimize control flow divergence, as each thread should ideally follow the same path to avoid performance degradation.

let result = select(1.0, 0.0,condition); // Selects 1.0 if condition is true, else 0.0This ensures that no branches are taken, reducing potential control flow divergence.

One of the most common issues when moving from GLSL to WGSL in fragment shaders is handling control flow. In GLSL, branching (e.g., if-else) is straightforward. However, in WGSL, when using a GPU’s parallel processing capabilities, branching can lead to control flow divergence, where different threads within a workgroup follow different execution paths.

This can negatively impact performance, as GPUs typically perform best when all threads within a workgroup execute the same code. To minimize control flow divergence, we need to consider alternatives to if-else statements, such as using functions like select() and reducing the complexity of conditional logic.

Instead of using if-else, you can use select() to handle conditions more efficiently. Here's an example of how you might convert a simple if-else into a select():

GLSL with if-else:

if (distance < 0.1) {

color = vec3(1.0, 0.0, 0.0); // Red

} else {

color = vec3(0.0, 1.0, 0.0); // Green

}WGSL with select():

color = select(vec3(1.0, 0.0, 0.0), vec3(0.0, 1.0, 0.0),distance < 0.1); // Red if distance < 0.1, else greenIn this case, we use .select() to eliminate the need for branching, allowing all threads to follow the same execution path.

In WGSL, logical functions are essential for handling parallelism efficiently, especially when you need to avoid branching. Functions like all(), any(), select(), and bitwise operations can help you write more optimized and readable shaders, allowing the GPU to execute your code in parallel without divergence. These functions are invaluable for anyone transitioning from GLSL to WGSL, where parallel execution and performance are more explicit and critical.

WGSL offers a refined and often more powerful approach to mathematical operations compared to GLSL. This section dives into the key advantages and differences you'll encounter when working with math in WGSL, with a special focus on the fused multiply-add (fma()) operation and its implications for shader performance.

The Fused Multiply-Add (FMA) operation is a GPU-accelerated instruction that combines multiplication and addition into a single step. This not only improves performance but also enhances precision by reducing intermediate rounding errors.

The function signature in WGSL looks like this:

fn fma(e1: T, e2: T, e3: T) -> T

This performs the operation

In raymarching, especially when calculating the distance between the ray and various objects, FMA can be used to update the intersection point calculations. Here's a simplified example:

let rayDirection = vec3<f32>(1.0, 0.0, 0.0);

let distanceToObject = fma(rayDirection.x, rayDirection.x, 1.0); // fma(x * x + 1.0)Here, FMA calculates x^2 + 1 in one operation, instead of using separate multiplication and addition steps.

The use of FMA is pivotal in several areas of graphics programming, such as:

-

Reduced Floating-Point Error: By combining multiplication and addition into one step, FMA minimizes rounding errors, which can be significant when performing many sequential computations.

-

Performance Optimization: Most GPUs have hardware support for FMA, allowing it to execute faster than separate multiplication and addition instructions.

-

Streamlined Shader Logic: Many graphics algorithms, like lighting calculations or raymarching, involve repetitive arithmetic operations. Using FMA reduces the instruction count, improving shader throughput.

Raymarching involves calculating the distance from a ray to various objects in the scene iteratively. FMA is especially useful here for updating the total distance along the ray:

// Example: Using FMA in raymarching

let stepSize = min(sphereDist, planeDist);

totalDist = fma(stepSize, 1.0, totalDist); // totalDist += stepSize

ro += rd * stepSize; // Move the ray forwardThis single operation replaces the equivalent totalDist += stepSize; and ensures precision when accumulating floating-point distances over multiple iterations.

In lighting calculations, such as Phong shading, combining diffuse, specular, and ambient components is a common task. With FMA, we can simplify and optimize these computations:

// Phong shading using FMA

let diffuse = max(dot(lightDir, normal), 0.0);

let specular = pow(max(dot(reflectionDir, viewDir), 0.0), shininess);

// Combine lighting components efficiently with FMA

let lighting = fma(diffuse, diffuseColor, fma(specular, specColor, ambientColor));

This replaces:

let lighting = diffuse * diffuseColor + specular * specColor + ambientColor;Here, FMA reduces the computation to just two fused operations, minimizing floating-point error and improving efficiency.

WGSL doesn't stop at FMA. It provides a richer set of mathematical tools compared to GLSL, leading to more efficient and precise shaders:

-

Comprehensive Built-in Functions: WGSL offers a wider array of built-in functions for trigonometry, exponentiation, logarithms, clamping, stepping, geometric operations, and interpolation. This reduces the need for custom function implementations and improves code readability.

-

Explicit Precision and Types: WGSL enforces explicit types like

f32,i32, andu32, giving you finer control over precision and memory usage. This contrasts with GLSL's precision qualifiers, which can be less intuitive. -

Efficient Vector Operations: WGSL excels at component-wise vector operations, enabling SIMD optimizations that are crucial for GPU performance. This allows for concise and efficient code when dealing with vectors and matrices.

-

Stricter Type Handling: WGSL's strict type system, with no implicit conversions, ensures greater code clarity and reduces potential errors that can arise from unexpected type conversions in GLSL.

In GLSL, precision qualifiers like lowp, mediump, and highp give you some control over precision but often lack clarity and consistency across different hardware. The ambiguity of these qualifiers can lead to unexpected behavior or suboptimal performance, particularly on platforms with different GPU architectures.

WGSL addresses this limitation with an explicit and straightforward type system. Instead of relying on imprecise qualifiers, WGSL defines precision directly through its types. For example:

f32for 32-bit floating-point numbersi32for 32-bit signed integersu32for 32-bit unsigned integers

This explicit typing ensures consistency across devices, improves shader clarity, and offers better control over memory usage and performance.

The explicit types in WGSL provide several benefits over GLSL's qualifiers:

-

Clarity and Readability: The precision is always unambiguous. When you see

f32, you know it's a 32-bit float—no guesswork required. -

Portability: Unlike GLSL's qualifiers, which can vary in behavior across devices, WGSL types behave consistently, ensuring that your shaders produce the same results on all platforms.

-

Optimization Potential: By explicitly defining the types, the compiler can optimize memory usage and execution more effectively, leading to better performance.

-

Error Prevention: WGSL's strict type checking helps catch errors at compile time, such as mismatched types or unintended precision reductions.

Here's how WGSL's explicit types shine in various mathematical operations:

// Example using trigonometry (f32 precision)

fn calculateWaveOffset(time: f32, speed: f32, amplitude: f32) -> f32 {

let angle = time * speed;

return sin(angle) * amplitude;

}

// Example using clamping (i32 precision)

fn clampColorComponent(value: i32) -> i32 {

return clamp(value, 0, 255);

}

// Example using geometric functions (vec3<f32> precision)

fn calculateReflection(incident: vec3<f32>, normal: vec3<f32>) -> vec3<f32> {

return reflect(incident, normal);

}With WGSL's typed precision system, you no longer need to worry about device-specific interpretations of lowp or mediump. Instead, you gain precise control over how each value is represented and processed. This is particularly important in ShaderToy-like projects, where achieving consistent visual results across platforms is critical.

While WGSL shares many concepts and structures with GLSL, transitioning between the two requires an understanding of some key differences. These differences not only impact how shaders are written but also provide opportunities to write cleaner, more precise, and more performant code.

- No Swizzling

In GLSL, you might be accustomed to using swizzling to manipulate vector components concisely, likevec.xy,vec.yx, or even chaining, such asvec.xyyz. WGSL simplifies this by requiring explicit access to vector components using dot notation (vec.x,vec.y, etc.). While this may initially feel restrictive, it promotes clarity and reduces ambiguity in shader code.

GLSL Example:

vec4 color = texture(sampler2D, uv).rgba;

vec3 modified = color.rgb.yzx; // Swizzling to rearrange componentsWGSL Equivalent:

let color = textureSample(texture, sampler, uv);

let modified = vec3<f32>(color.y, color.z, color.x); // Explicitly rearranging componentsFunction Overloading Differences

While GLSL supports function overloading extensively, WGSL's approach is more structured. Some functions in WGSL may have different parameter orders or fewer overloads than their GLSL counterparts. Always refer to the WGSL specification to ensure correct usage.

GLSL Example:

float luminance = dot(vec3(0.299, 0.587, 0.114), color.rgb); // Overloaded dot productWGSL Equivalent:

let luminance = dot(vec3<f32>(0.299, 0.587, 0.114), color.rgb); // Explicit type annotation

No Implicit Conversions

Unlike GLSL, WGSL does not perform implicit type conversions. For example, you cannot pass an i32 where an f32 is expected without explicit casting. This makes type mismatches more obvious but requires more verbose code in some cases.

GLSL Example:

float result = 0.5 + intValue; // Implicit conversion of intValue to floatWGSL Equivalent:

let result = 0.5 + f32(intValue); // Explicit cast requiredWGSL's stricter syntax and type system might feel limiting at first, but these changes enforce good practices that ultimately result in more robust and performant shaders. By adapting to WGSL’s:

- Typed precision system (e.g.,

f32,i32), - Explicit access patterns,

- Built-in functions designed for precision and efficiency,

you can write shaders that are optimized for the WebGPU pipeline and modern GPU architectures.

- Start Small: Begin by porting simpler GLSL shaders to WGSL, focusing on understanding explicit types, vector access, and function calls.

- Use Built-In Tools: Leverage IDEs and compilers that support WGSL syntax checking and auto-completion.

- Test Thoroughly: Differences in type handling and precision can lead to subtle bugs. Test your shaders on multiple devices to ensure consistency.

- Study the Specification: The WGSL specification is a valuable resource for understanding subtle differences and leveraging WGSL’s unique features.

In WGSL, function parameters are immutable by default. While this promotes safer and more predictable code, it can be a hurdle when you're used to GLSL, where modifying parameters directly is common practice. For example, you might want to manipulate a vec3<f32> parameter inside a function without affecting its original value.

In cases like these, WGSL requires a bit of extra care. Here are three practical approaches you can use to handle this situation:

You can reassign the parameter to a local variable . This creates a new variable in the local scope, effectively "shadowing" the original immutable parameter.

fn map(p: vec3<f32>) -> vec4<f32> {

var mutable_p = p; // Shadows the parameter with a mutable local variable.

mutable_p.y += 0.6;

return vec4<f32>(mutable_p, 1.0);

}- Leveraging Pointers for Advanced Use Cases

For scenarios requiring in-place modifications or passing variables between functions, pointers can be a powerful alternative. Instead of passing the parameter directly, you pass a pointer to it.

fn modify_p(p_ptr: ptr<function, vec3<f32>>) {

(*p_ptr).y += 0.6; // Dereference the pointer to modify the value.

}

fn map(p: vec3<f32>) -> vec4<f32> {

var mutable_p = p;

modify_p(&mutable_p); // Pass a pointer to `mutable_p`.

return vec4<f32>(mutable_p, 1.0);

}Using pointers makes your intentions explicit and provides more flexibility, especially when functions need to modify the same object.

By adopting these patterns, you can handle immutable parameters gracefully in WGSL. Choosing the right approach depends on your specific use case:

- Use shadowing for quick modifications in small functions.

- Leverage pointers for advanced operations requiring in-place modifications.

When transitioning from GLSL to WGSL, one important rule to follow is to avoid if-then-else statements, especially inside performance-critical shaders. Here's why:

- Dynamic Branching and Performance:

GPUs are optimized for parallel execution. When you useif-then-elsestatements, especially in shaders that process large amounts of data (like in raymarching or particle systems), the execution can diverge. This means that different threads (or work items) in the same workgroup will execute different code paths. This divergence can lead to inefficient GPU utilization as the hardware may have to process both paths serially rather than in parallel. - WGSL's Focus on Parallelism:

WGSL is designed with parallelism in mind, and it's typically more efficient to leverage arithmetic operations that don't depend on conditional branching. This keeps threads running in lockstep, reducing idle time and improving throughput.

Using Ternary Operators: A common pattern in WGSL is to use ternary operators (condition ? expr1 : expr2) for simpler conditional assignments. This doesn't introduce control flow divergence and can often be as efficient as direct branching.

var col: vec3<f32> = (condition) ? vec3<f32>(1.0, 0.0, 0.0) : vec3<f32>(0.0, 0.0, 1.0);Use of select() Function: For more complex conditions, WGSL's select() function can be a good alternative. select() performs a conditional assignment without creating control flow divergence, which is much more efficient.

var result: f32 = select(a, b, condition);This will assign a if condition is true, or b if condition is false, but without introducing branching.

Mathematical Workarounds: Where possible, try to refactor if-else logic into mathematical expressions. For example, using min(), max(), or mix() to handle conditional logic instead of actual branching.

var col: vec3<f32> = mix(vec3<f32>(0.0, 0.0, 1.0), vec3<f32>(1.0, 0.0, 0.0), condition);This avoids control flow divergence and keeps the shader parallelizable.

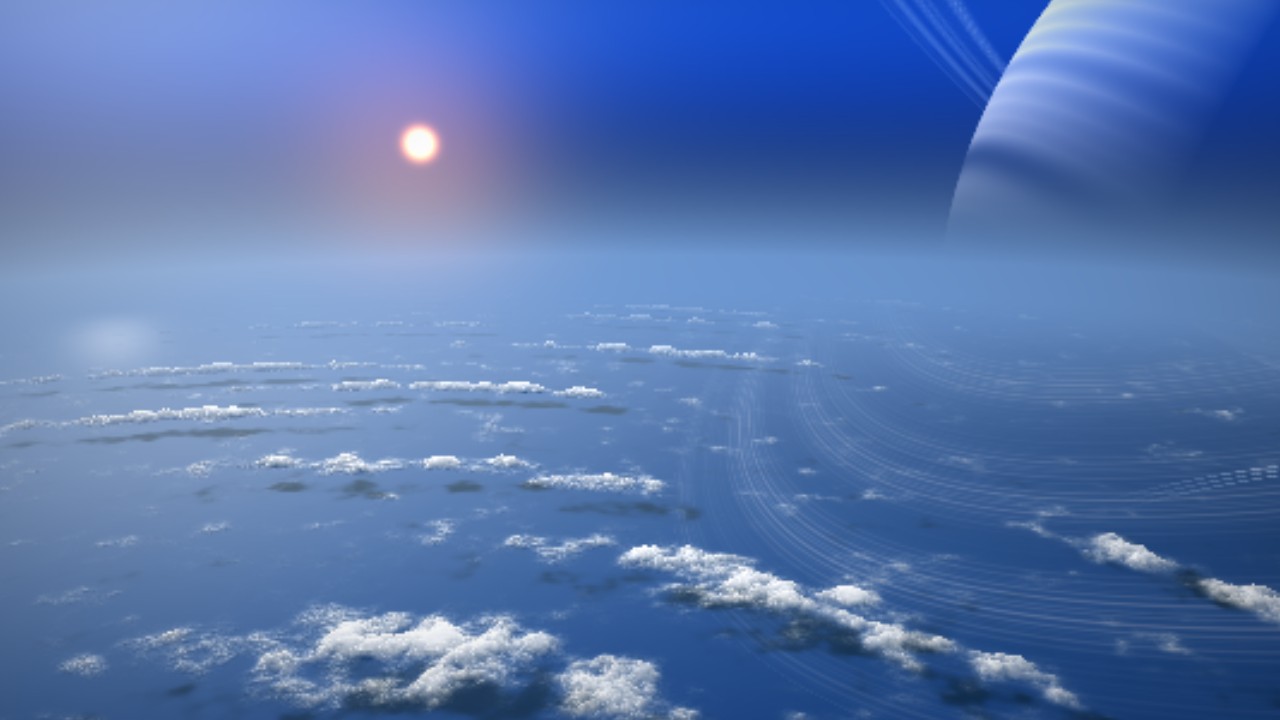

Let's dig in to a convert one of Mrange's stunning raymarched scenes, originally written in GLSL, to WGSL (WebGPU Shading Language). The original shader Alien Waterworld, can be found on ShaderToy here: https://www.shadertoy.com/view/WtXyW4. This may perhaps be if interest i do belive.

One of the first things encountered during the conversion process was dealing with constants and macros defined using #define in the original GLSL code. WGSL does not support preprocessor directives like #define, so I had to find alternative ways to represent these values.

Here's a comparison of how some of the constants and macros were defined in GLSL and how I translated them to WGSL:

GLSL

#define PI 3.141592654

#define TAU (2.0*PI)

#define TOLERANCE 0.00001

#define MAX_ITER 55

#define MAX_DISTANCE 31.0

#define PERIOD 45.0

#define TIME mod(iTime, PERIOD)

const vec3 skyCol1 = vec3(0.35, 0.45, 0.6);

// ... other constants ...

**WGSL**

const PI: f32 = 3.1415927;

const TAU: f32 = 2.0 * PI;

const MAX_ITER: i32 = 55;

const TOLERANCE: f32 = 0.00001;

const MAX_DISTANCE: f32 = 31.0;

const PERIOD: f32 = 45.0;

fn TIME() -> f32 {

return uniforms.time % PERIOD;

}

const skyCol1: vec3<f32> = vec3<f32>(0.35, 0.45, 0.6);

// ... other constants ...

Explanation

-

Constants: The simple constants like

PI,TAU,MAX_ITER, etc., are directly translated to WGSL using theconstkeyword and appropriate types (e.g.,f32for floats,i32for integers). -

Macros: The

TIMEmacro, which involves a calculation, is converted to a WGSL functionTIME(). This function performs the same modulo operation as the macro. Note we will not use it, but i wanted to illustrate it anyhow. We will be using a direct calculation instead. -

Vectors: The

vec3constants are translated to WGSL using thevec3<f32>type.

The mainImage() function is the core of the shader, where the scene is rendered and colors are calculated. Let's compare the original GLSL version with the converted WGSL version, highlighting the key differences and optimizations.

GLSL

void mainImage(out vec4 fragColor, vec2 fragCoord) {

vec2 q = fragCoord.xy/iResolution.xy;

vec2 p = -1.0 + 2.0*q;

p.x *= iResolution.x/iResolution.y;

vec3 col = getSample1(p, TIME);

col = postProcess(col, q);

col *= smoothstep(0.0, 2.0, TIME);

col *= 1.0-smoothstep(PERIOD-2.0, PERIOD, TIME);

fragColor = vec4(col, 1.0);

}WGSL

fn mainImage(invocation_id: vec2<f32>) -> vec4<f32> {

// Inline TIME calculation

let timeMod: f32 = uniforms.time % PERIOD; // Direct calculation, removing external function call

// Screen resolution from uniforms

let R: vec2<f32> = uniforms.resolution.xy;

// Compute the y-inverted location and original location in pixel space

let y_inverted_location: vec2<i32> = vec2<i32>(

i32(invocation_id.x),

i32(R.y) - i32(invocation_id.y)

);

let location: vec2<i32> = vec2<i32>(i32(invocation_id.x), i32(invocation_id.y));

// Initialize fragment coordinates

let fragCoord = vec2<f32>(

invocation_id.x,

uniforms.resolution.y - invocation_id.y

);

// Compute normalized device coordinates

let q: vec2<f32> = fragCoord.xy / uniforms.resolution.xy;

var p: vec2<f32> = -1.0 + 2.0 * q;

p.x = p.x * (uniforms.resolution.x / uniforms.resolution.y);

var col: vec3<f32> = getSample1(p, timeMod);

// Post-processing effects

col = postProcess(col, q);

col = col * smoothstep(0.0, 2.0, timeMod);

col = col * (1.0 - smoothstep(PERIOD - 2.0, PERIOD, timeMod));

// Return the final color as a vec4

return vec4<f32>(col, 1.0);

}**Explanation **

- Function signature:

- In GLSL,

mainImage()takes anout vec4 fragColorparameter to output the fragment color. - In WGSL,

mainImage()returns avec4<f32>value representing the fragment color.

- In GLSL,

TIMEmacro:- In GLSL, the

TIMEmacro is used to calculate the time value. - In WGSL, the

TIMEmacro is replaced with an inline calculationuniforms.time % PERIOD. This eliminates the need for a separate function call and can potentially improve performance.

- In GLSL, the

- Variable declarations: WGSL requires explicit variable declarations with type annotations (e.g.,

var col: vec3<f32>).

The getSample1() function plays a crucial role in setting up the scene for the raymarching process. It defines the camera position, ray direction, and calls the getColor() function (which we'll explore later) to determine the color of the scene based on the ray.

GLSL

vec3 getSample1(vec2 p, float time) {

// ... (define ro, la, ww, uu, vv) ...

vec3 rd = normalize(p.x*uu + p.y*vv + 2.0*ww);

vec3 col = getColor(ro, rd);

return col;

}WGSL

fn getSample1(p: vec2<f32>, time: f32) -> vec3<f32> {

// ... (define ro, la, ww, uu, vv) ...

// Use fma for rd calculation: p.x * uu + p.y * vv + 2.0 * ww

let rd: vec3<f32> = normalize(fma(vec3<f32>(p.x), uu, fma(vec3<f32>(p.y), vv, 2.0 * ww)));

var col: vec3<f32> = getColor(ro, rd);

return col;

}Explanation

- Function signature:

- In GLSL, the function takes

vec2 pandfloat timeas arguments and returns avec3. - In WGSL, the function takes

p: vec2<f32>andtime: f32as arguments and returns avec3<f32>, with explicit type annotations.

- In GLSL, the function takes

fma()function:- In WGSL, the

fma()(fused multiply-add) function is used for the calculation ofla.yandrd. This function performs a multiplication and addition in a single operation, which can be more efficient than separate operations on some GPUs.

- In WGSL, the

- Variable declarations: WGSL requires explicit variable declarations with type annotations (e.g.,

let rd: vec3<f32>).

The use of the fma() function is an example of how WGSL can be optimized for WebGPU.

The getColor() function is where Mårtens magic of raymarching happens. It takes the camera's position and ray direction, then marches along the ray, calculating the color of the scene based on the objects it intersects. ( We will look at the marcher also)

GLSL

vec3 getColor(vec3 ro, vec3 rd) {

int max_iter = 0;

vec3 skyCol = skyColor(ro, rd);

vec3 col = vec3(0);

const float shipHeight = 1.0;

const float seaHeight = 0.0;

const float cloudHeight = 0.2;

const float upperCloudHeight = 0.5;

float id = (cloudHeight - ro.y)/rd.y;

if (id > 0.0) {

float d = march(ro, rd, id, max_iter);

vec3 sunDir = sunDirection();

vec3 osunDir = sunDir*vec3(-1.0, 1.0, -1.0);

vec3 p = ro + d*rd;

float loh = loheight(p.xz, d);

float loh2 = loheight(p.xz+sunDir.xz*0.05, d);

float hih = hiheight(p.xz, d);

vec3 normal = normal(p.xz, d);

float ud = (upperCloudHeight - 4.0*loh - ro.y)/rd.y;

float sd = (seaHeight - ro.y)/rd.y;

vec3 sp = ro + sd*rd;

float scd = (cloudHeight - sp.y)/sunDir.y;

vec3 scp = sp + sunDir*scd;

float sloh = loheight(scp.xz, d);

float cshd = exp(-15.0*sloh);

float amb = 0.3;

vec3 seaNormal = normalize(vec3(0.0, 1.0, 0.0));

vec3 seaRef = reflect(rd, seaNormal);

vec3 seaCol = .25*skyColor(p, seaRef);

seaCol += pow(max(dot(seaNormal, sunDir), 0.0), 2.0);

seaCol *= cshd;

seaCol += 0.075*pow(vec3(0.1, 1.3, 4.0), vec3(max(dot(seaNormal, seaRef), 0.0)));

float spe = pow(max(dot(sunDir, reflect(rd, normal)), 0.0), 3.0);

float fre = pow(1.0-dot(normal, -rd), 2.0);

col = seaCol;

const float level = 0.00;

const float level2 = 0.3;

// REALLY fake shadows and lighting

vec3 scol = sunCol1*(smoothstep(level, level2, hih) - smoothstep(level, level2, loh2));

col = mix(vec3(1.0), col, exp(-17.0*(hih-0.25*loh)));

col = mix(vec3(.75), col, exp(-10.0*loh*(max(d-ud, 0.0))));

col += scol;

col += vec3(0.5)*spe*fre;

float ssd = (shipHeight - ro.y)/rd.y;

col += shipColor((ro + rd*ssd).xz);

col = mix(col, skyCol, smoothstep(0.5*MAX_DISTANCE, 1.*MAX_DISTANCE, d));

} else {

col = skyCol;

}

return col;

}WGSL

fn skyColor(ro: vec3<f32>, rd: vec3<f32>) -> vec3<f32> {

let sunDir: vec3<f32> = sunDirection();

let smallSunDir: vec3<f32> = smallSunDirection();

let sunDot: f32 = max(dot(rd, sunDir), 0.0);

let smallSunDot: f32 = max(dot(rd, smallSunDir), 0.0);

// Avoid recomputing length(rd.xz)

let rdXZLength: f32 = length(rd.xz);

let angle: f32 = atan(rd.y / rdXZLength) * (2.0 / PI);

let sunCol: vec3<f32> =

0.5 * sunCol1 * pow(sunDot, 20.0) +

8.0 * sunCol2 * pow(sunDot, 2000.0);

let smallSunCol: vec3<f32> =

0.5 * smallSunCol1 * pow(smallSunDot, 200.0) +

8.0 * smallSunCol2 * pow(smallSunDot, 20000.0);

// Ray-sphere and ray-plane intersections

let si: vec2<f32> = raySphere(ro, rd, planet);

let pi: f32 = rayPlane(ro, rd, rings);

// Dust transparency and sky color blending

let dustTransparency: f32 = smoothstep(-0.15, 0.075, rd.y);

let skyCol: vec3<f32> = mix(

skyCol1 * (1.0 - dustTransparency),

skyCol2 * sqrt(dustTransparency),

sqrt(dustTransparency)

);

// Planet-related calculations

let planetSurface: vec3<f32> = ro + si.x * rd;

let planetNormal: vec3<f32> = normalize(planetSurface - planet.xyz);

let planetDiff: f32 = max(dot(planetNormal, sunDir), 0.0);

let planetBorder: f32 = max(dot(planetNormal, -rd), 0.0);

let planetLat: f32 = (planetSurface.x + planetSurface.y) * 0.0005;

let planetCol: vec3<f32> = mix(

1.3 * planetCol,

0.3 * planetCol,

pow(

psin(planetLat + 1.0) *

psin(sqrt(2.0) * planetLat + 2.0) *

psin(sqrt(3.5) * planetLat + 3.0),

0.5

)

);

// Rings calculations

let ringsSurface: vec3<f32> = ro + pi * rd;

let ringsDist: f32 = length(ringsSurface - planet.xyz);

let ringsPeriod: f32 = ringsDist * 0.001;

let ringsMul: f32 = pow(

psin(ringsPeriod + 1.0) *

psin(sqrt(0.5) * ringsPeriod + 2.0) *

psin(sqrt(0.45) * ringsPeriod + 4.0) *

psin(sqrt(0.35) * ringsPeriod + 5.0),

0.25

);

let ringsMix: f32 = psin(ringsPeriod * 10.0) *

psin(ringsPeriod * 10.0 * sqrt(2.0)) *

(1.0 - smoothstep(50000.0, 200000.0, pi));

let ringsCol: vec3<f32> = mix(

vec3<f32>(0.125),

0.75 * ringColor,

ringsMix

) * step(-pi, 0.0) *

step(ringsDist, 150000.0 * 0.655) *

step(-ringsDist, -100000.0 * 0.666) *

ringsMul;

// Combine results

let borderTransparency: f32 = smoothstep(0.0, 0.1, planetBorder);

var result: vec3<f32> = vec3<f32>(0.0);

result = result + ringsCol * (step(pi, si.x) + step(si.x, 0.0));

result = result + step(0.0, si.x) *

pow(planetDiff, 0.75) *

mix(planetCol, ringsCol, 0.0) *

dustTransparency *

borderTransparency +

ringsCol * (1.0 - borderTransparency);

result = result + (skyCol + sunCol + smallSunCol);

return result;

}

Explanation Function signature and variable declarations, but i guess i dont need to mention that agian, i did try to optimize, but i probably ruined Mårtens work.

-

Precomputed Values:

- Cached

length(rd.xz)asrdXZLengthfor reuse. - Simplified calculations by reducing repeated expressions.

- Cached

-

Efficient Blending:

- Consolidated and optimized the

mixandsmoothstepoperations for sky and dust transparency.

- Consolidated and optimized the

-

Precision (

fmaUse):- Where applicable,

fmacan further reduce numerical error, though not always used here for simplicity.

- Where applicable,

The heart of the raymarching algorithm lies in the march() function. This function takes the camera's position, ray direction, and an initial distance as input. It then "marches" along the ray, step by step, until it hits an object in the scene or reaches a maximum distance.

The march() function calculates the distance to the nearest object at each step and adjusts the ray's position accordingly. This process continues until the ray either intersects an object (within a certain tolerance) or travels beyond the maximum distance.

GLSL

float march(vec3 ro, vec3 rd, float id, out int max_iter) {

float dt = 0.1;

float d = id;

int currentStep = 0;

float lastd = d;

for (int i = 0; i < MAX_ITER; ++i) {

vec3 p = ro + d*rd;

float h = height(p.xz, d);

if (d > MAX_DISTANCE) {

max_iter = i;

return MAX_DISTANCE;

}

float hd = p.y - h;

if (hd < TOLERANCE) {

return d;

}

float sl = 0.9;

dt = max(hd*sl, TOLERANCE+0.0005*d);

lastd = d;

d += dt;

}

max_iter = MAX_ITER;

return MAX_DISTANCE;

}

WGSL

fn march(ro: vec3<f32>, rd: vec3<f32>, id: f32, max_iter: ptr<function, i32>) -> f32 {

var dt: f32 = 0.1;

var d: f32 = id;

var lastd: f32 = d;

for (var i: i32 = 0; i < MAX_ITER; i = i + 1) {

let p: vec3<f32> = ro + d * rd;

let h: f32 = height(p.xz, d);

// Use any() to combine conditions

if (any(vec2<bool>(d > MAX_DISTANCE, p.y - h < TOLERANCE))) {

*max_iter = i;

return select(MAX_DISTANCE, d, p.y - h < TOLERANCE);

}

let sl: f32 = 0.9;

dt = max(p.y - h * sl, TOLERANCE + 0.0005 * d);

lastd = d;

// Use fma() for more efficient calculation

d = fma(1.0, dt, d);

}

*max_iter = MAX_ITER;

return MAX_DISTANCE;

}Explanation

- Function signature:

- GLSL:

float march(vec3 ro, vec3 rd, float id, out int max_iter) - WGSL:

fn march(ro: vec3<f32>, rd: vec3<f32>, id: f32, max_iter: ptr<function, i32>) -> f32(explicit types, pointer formax_iter)

- GLSL:

max_iter:- GLSL: Uses an

out int max_iterparameter to output the maximum iterations. - WGSL: Uses a pointer (

ptr<function, i32>) to passmax_iterby reference.

- GLSL: Uses an

- Branching:

- GLSL: Uses an

ifstatement with a nestediffor the conditions. - WGSL: Uses the

any()function to combine the conditions andselect()to choose the return value based on which condition was met. This can be more efficient on GPUs by avoiding branching.

- GLSL: Uses an

fma()function:- WGSL: Uses the

fma()(fused multiply-add) function for thed += dtcalculation. This can be more efficient on some GPUs by combining the multiplication and addition into a single operation.

- WGSL: Uses the

In addition to the core functions like getColor() and march(), the original GLSL shader utilized several utility functions for common operations such as rotation, periodic functions, and coordinate conversions. These functions needed to be adapted to WGSL as well.

Here's a comparison of some of these utility functions in GLSL and their WGSL counterparts.

GLSL

void rot(inout vec2 p, float a) {

float c = cos(a);

float s = sin(a);

p = vec2(p.x*c + p.y*s, -p.x*s + p.y*c);

}

float psin(float f) {

return 0.5 + 0.5*sin(f);

}

vec2 toRect(vec2 p) {

return p.x*vec2(cos(p.y), sin(p.y));

}

vec2 toPolar(vec2 p) {

return vec2(length(p), atan(p.y, p.x));

}

float mod1(inout float p, float size) {

float halfsize = size*0.5;

float c = floor((p + halfsize)/size);

p = mod(p + halfsize, size) - halfsize;

return c;

}WGSL

fn rot(p: ptr<function, vec2<f32>>, a: f32) {

let c: f32 = cos(a);

let s: f32 = sin(a);

(*p) = vec2<f32>((*p).x * c + (*p).y * s, -(*p).x * s + (*p).y * c);

}

fn psin(f: f32) -> f32 {

return 0.5 + 0.5 * sin(f);

}

fn toRect(p: vec2<f32>) -> vec2<f32> {

return p.x * vec2<f32>(cos(p.y), sin(p.y));

}

fn toPolar(p: vec2<f32>) -> vec2<f32> {

return vec2<f32>(length(p), atan2(p.y, p.x));

}

fn mod1(p: ptr<function, f32>, size: f32) -> f32 {

let halfsize: f32 = size * 0.5;

// Read the value from the pointer

var value: f32 = *p;

// Perform the calculations

let c: f32 = floor((value + halfsize) / size);

value = ((value + halfsize) % size) - halfsize;

// Write the modified value back to the pointer

*p = value;

return c;

}Explanation

rot()function:- GLSL: Uses an

inout vec2 pparameter to modify the vector in place. - WGSL: Uses a pointer (

ptr<function, vec2<f32>>) to pass the vector by reference and modify it within the function.

- GLSL: Uses an

mod1()function:- GLSL: Uses an

inout float pparameter to modify the value in place. - WGSL: Uses a pointer (

ptr<function, f32>) to achieve the same in-place modification.

- GLSL: Uses an

- Type annotations: WGSL requires explicit type annotations for function parameters and return values.

- Built-in functions: Some built-in functions might have different names or behaviors in WGSL (e.g.,

atan()vs.atan2()).

This case study has brought together many of the key concepts we've explored throughout this post. We've seen how WGSL's stricter type system, structured uniform handling, and focus on parallel execution translate into practical code. From the basic syntax differences to the use of functions like select() and fma() for optimized performance, this example provides a clear picture of how to effectively transition from GLSL to WGSL, particularly for complex shader techniques like raymarching. This practical application should empower ShaderToy users and graphics programmers alike to start experimenting with WebGPU and WGSL.

You can fiddle with the thinng here

WGSL is more than just another shading language; it’s a deliberate evolution, designed to align with modern GPU architectures and WebGPU's vision of portable, high-performance graphics and compute. Transitioning from GLSL to WGSL can feel like stepping into a new paradigm, but the journey is both rewarding and necessary for future-ready shader development.

At its core, WGSL prioritizes clarity and precision. Unlike GLSL, WGSL avoids implicit behaviors, requiring you to write shaders that are explicit and unambiguous. This shift brings about stricter typing, removal of features like swizzling, and the need for structured handling of variables and functions. These changes might seem daunting at first, but they foster more robust and predictable code.

A recurring theme in this transition is parallelism. GPUs thrive on executing massive numbers of threads simultaneously, and WGSL reflects this by encouraging patterns that minimize divergence. Instead of relying on constructs like if-then-else, WGSL promotes alternatives such as select() to maintain performance while achieving the same outcomes.

On the practical side, adapting to WGSL involves adopting new approaches to familiar problems. Immutable function parameters, for example, require techniques like shadowing or local variables to enable flexible manipulation. Additionally, WGSL encourages efficient math operations—like fma—that make the most of GPU hardware.

The journey from GLSL to WGSL isn’t just about syntax; it’s about adopting a mindset that embraces the future of GPU programming. WGSL’s design principles ensure shaders are portable, optimized for the web, and built to leverage the full potential of modern GPUs. By understanding its nuances and adapting your workflow, you’ll not only create better shaders but also future-proof your skills in a rapidly evolving ecosystem.

In this post, we’ve explored WGSL’s differences, best practices, and even dived into optimizing real-world shader code. The goal was to demystify WGSL and equip you to start writing shaders that are as efficient as they are expressive.

The transition might demand some adjustments, but the result is clear: WGSL is paving the way for a new generation of graphics and compute on the web. Dive in, experiment, and embrace the future! 🚀

The original GLSL Shader by Mårten Rånge used in the Case Study https://www.shadertoy.com/view/WtXyW4

Run the a WGSL version of Alien Waterworld by Mårten Rånge https://magnusthor.github.io/demolished-rail/wwwroot/example/runsWGSLShader.html

Fiddle with the Alien Waterworld WGSL Shader

WGSL Function Reference https://webgpufundamentals.org/webgpu/lessons/webgpu-wgsl-function-reference.html